It’s Hard to be Thirteen

Rebecca fumed silently. Nothing could be better than having Daddy home, except if Levi had come with him. After the third full day’s work and once Mary Rachel and Gwendolyn’s breathing eased into a rhythmic chorus, she turned up her lamp and carried it to her desk. She retrieved paper and ink, then dipped her quill and wrote in a swoopy loopy cursive. She loved how pretty she could write.

May 29, 1836

Levi Bartholomew Baylor –

Why didn’t you come home before you lit a shuck to join the stupid rangers? Daddy’s been home three days, and it’s taken me this long to calm down enough from being mad at you to write.

When I first looked out and saw him riding in alone—without you—my heart stopped. I thought you were… Never you mind what I thought. You should have come home! We prayed for you and Daddy every day and night. Do you know how worried we were?

The night breeze caused the light curtain to dance. She looked up and gazed out the window at the stars, then sighed. She wasn’t really ever worried…

Well, as you know Mama always says worrying only hinders every promise of God, but you know what I mean. Of course we trust God to watch over and keep you—even if you are nothing but a heathen. And now you’ve gone and signed up to put yourself in more danger. I hate it! What’s wrong with you?

I hate you being gone. And I hate how angry I am with you that you made me think for even one minute that you were…

Oh, bosh! That’s all I’m writing tonight because I know all I’m doing is gripping and complaining. Mama told me men folk don’t like that and even the Bible says it’s better to live in the corner of an attic, than in a big house with a nagging woman! I’ll write more when my insides are calmer.

I had something I really wanted to talk with you that I’m all balled up over, but now you’re not here and you’re not coming home. You best be proud I love you so much, ’cause if I didn’t, I’d hate your guts for sure and certain.

Your teenaged sister, Rebecca

What would he think about her being in love? Lifting the partial page of writing, she waved it in the air, blowing gently on it while she corked the inkwell. She wanted to ask him about the best way to tell Chester Robbins how handsome he was, and how wonderful she thought he was. Once the ink dried, she folded the paper, stuck it inside her novel, and climbed into bed next to Mary Rachel. Sure would be nice to have her own room.

June 7, 1836

Me again. I guess I’m not angry with you anymore, but I’m still very sad. I don’t know when Daddy will want to post my letter, but I’ll keep writing until he does. May be my first book! He says we have to send it to the Ranger Office at Washington-on-the-Brazos, and you can pick it up when you’re by there. So I guess I won’t know when you might actually get it.

I can tell I am not going to like this arrangement. I miss you so much every day. Things here are getting back to normal. Nothing will ever be normal again though without you here. Can’t you just come home?

Daddy’s working on the house again. Him and Mama said I could go ahead and move into your room if I’ll box all your things. That’s a benefit to you being gone, but I’d rather have you here even if Mary Rachel is a terrible bed partner, rolling and kicking and climbing over me all night. Best hurry back or you won’t have a room to come home to.

She dipped her quill again. What did she want to tell him? What might he find interesting? How she could possibly persuade him to come back home and forget rangering altogether? What was it that caused men to like fighting and danger, wars and the like? She hated it all and wanted everyone to mind their own business and stay home and get married and have babies.

I guess you know since you aren’t here, me and Mama have to haul the boards up the ladder for Daddy. He’s putting on a second story to double the space and make bedrooms for all the baby girls. Anyway, it’s hard work for women to do, and if you were here, we wouldn’t have to.

Oh, and guess what! We have a cook now. Captain O’Mally sent them to Clarksville and Daddy picked them up from town. Are you wondering why I keep saying them? It’s on account of Mammy, that’s the cook, has a son. His name is Jean Paul, but he isn’t as dark skinned as her. He’s all grown up, older than you, and he knows powerful lot about cotton. They used to be slaves!

Can you imagine what it would be like if somebody owed you like we own our horses? Mammy said their old master’s done gone to Glory and he set them free in his will. Freedmen is what they are now. Don’t tell Mama I said, but Mammy sure can cook. Ha! You don’t even know what you’re missing? When are you coming home, Levi?

Gotta go, Mama’s calling me. Mary Rachel’s hollering, too. She’s really talking up a storm all of a sudden and says the cutest things. Ask me the other day if I ever ate a worm! If you don’t come back directly, she’s liable to forget who you are. Think you’ll be here afore summer’s gone? I hope so.

I love you and miss you heaps.

Your Bitti Beck

p.s. um, guess you figured out Jean Paul’s actually carrying most the boards now, but that’s no reason for you to stay gone!

“Long live the Republic, Levi! Now come home!”

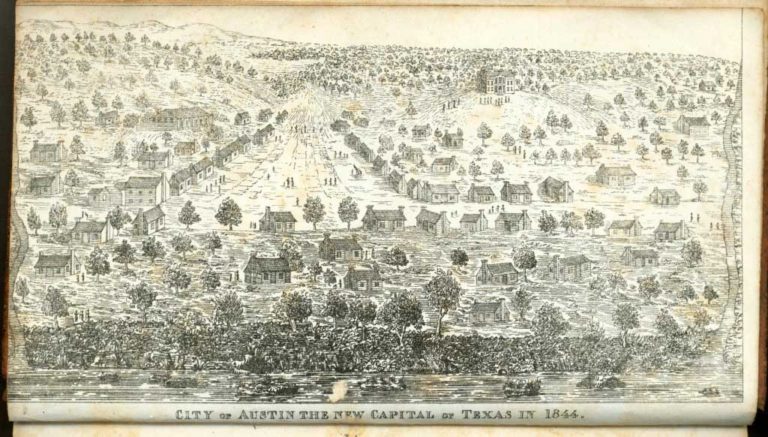

Daddy described this as our new flag.